Juror Statement

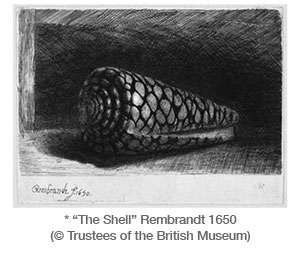

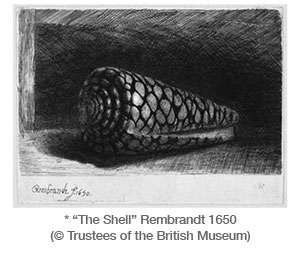

Linda Sokolowski: The sixties and seventies were years of intense enthusiasm among printmaker-painters for very large works on paper. Many printmakers were passionately using the newly designed gigantic rolls of heavily sized papers and coveting huge handmade sheets being produced to accommodate this new love. In 1970 in the heart of such intensity for the monumental in printmaking and drawing, I traveled to Jenkintown, Pennsylvania to the Rosenwald Collection (now housed in the National Gallery, Washington) to complete research for my graduate thesis in printmaking. It was there that I discovered the miniature. In my lap were boxes upon boxes of Rembrandt, many unique early states, all superb impressions, drawn on slices of copper as if he were working on the world’s largest available paper, though knowing well the secrets of telling his narrative with thirteen figures or more in a space that approximated or fell below the dimensions our printers were to abide by in this exhibition. “The Shell”*, a print I’ve returned to over and again with my students, begins as a simple cone shell against a white ground, and in succeeding states transforms itself into an ancient, elegant locomotive at rest in an abandoned, underground tunnel. Much of Rembrandt’s lesson lies in what we all know: a box seen as a box may appear as an object too small to step into; but that same box seen as an architectural structure can, through the power of visual organization, become a massive space with breathable air.

Rembrandt’s small prints (many 2” x 3”) were worked with the same openness and curiosity as his more rigorous images such as “Ecce Homo” and “The Three Crosses”. And yet the major large pieces are battlefields for ongoing change. The modifications are often vigorously dug directly on top of the narrative’s beginnings and are sometimes scraped away entirely, leaving only ghosts of first impressions. The miniatures, by contrast, seldom take a new route once begun. They are drawn with assurance, direct observation, and tenderness like swift studies in a master’s sketchbook. It is the incredible attention to touch, to sculpting as he draws through his ground, to the space dictated by the plate and to his alertness to his Dutch Mordant’s activity that encourages these small works to loom large. Nothing goes unattended. Nothing is cast off as the light in the tiny plate’s room beckons. It is something that is difficult to see unless you’ve observed the actual prints.

In the artist’s studio the miniature refreshes the monumental, and until quite recently it was utilized by almost everyone except the Abstract Expressionists (though DeKooning in the earliest years made small drawings, Kline returned to them in his middle years and Diebenkorn worked beautiful small representational drypoints and soft grounds). To illustrate his Pere Ubu series of miniature aquatint illustrations, Rouault charged his brushes with sugar lift ink and painted on copper. Goya, at age 79, on slivers of ivory that he covered with carbon, dropped a splash of water and searched for the nascent image, which he then developed as stunning monotype-like miniatures with little brushes. Durer, in his “Small Engraved Passion” cut with his burin what for me are his most moving engraved images. Rembrandt and Picasso (early on) used well-sharpened drypoint and etching tools. These tools and techniques were chosen in each artist’s studio to fit his own miniature staging areas, always as important to them as their major large work.

Exhibited in this show:

Sara Schleicher used tools that stumped me to complete her stunning series of umber monotypes which brought back childhood memories when I sat inside huge cocoons of fallen leaf piles in late October, lay back and looked through to the sky. But Schleicher adds another psychological element in the hidden growth with her hint of forewarning.

Harvey Breverman’s lively soft ground caricatures place us at talking distance to these famous men. In his tondo, in particular, we are very close to this head and remember where we sat in conversation. Breverman, as Rembrandt before him, knows touching distance, that is allowing his tool to believe it is actually on his figure.

Thom O’Connor’s lush, digital prints, probably the smallest images in the show, allow a long quiet stride through silver spaces between dark-figured trees, like walking through a perfectly balanced Morandi natura morte.

Jim Dormer in “Arezzo” moves with his burin through blinding Italian light invented by vibrations between the intersecting lines.

Sasja Lucas’ fresh, abstract monotypes set still life-like forms into landscape scale.

We walk on Mary Rose Griffin’s table between mixed media edibles defined subtly by drypoint. Her opened contours do not strangle the figures but build significant, substantial forms.

Thomas Seawell’s studio doors and Michael Arike’s handsome color etchings demonstrate strong beliefs in the miniature.

The size an artist assigns to each work determines the way we receive it. We hold the miniature to our faces or, if we can, place it in our lap. In a great print room with well-trained curatorial staff, the brilliant miniature possesses accessible open doors for one to enter privately. Our external environment should fall away so that we may read this image made, not with the whole body in motion, but rather with the tenacious pull of the fingers and wrist.

We thank Bev McLean for retaining the courage, enthusiasm and dedicated hours to have brought this exhibition to the Binghamton area year after year. She opened her home to these jurors and carefully unwrapped the prints and positioned them in alphabetical order by artist. It is not fashionable to sponsor a miniature print show; and the places that had become well known for theirs sadly, I believe, no longer participate. But some day they will again. Meanwhile, the belief in the miniature is kept alive in intimate, small circles.

Linda Sokolowski: The sixties and seventies were years of intense enthusiasm among printmaker-painters for very large works on paper. Many printmakers were passionately using the newly designed gigantic rolls of heavily sized papers and coveting huge handmade sheets being produced to accommodate this new love. In 1970 in the heart of such intensity for the monumental in printmaking and drawing, I traveled to Jenkintown, Pennsylvania to the Rosenwald Collection (now housed in the National Gallery, Washington) to complete research for my graduate thesis in printmaking. It was there that I discovered the miniature. In my lap were boxes upon boxes of Rembrandt, many unique early states, all superb impressions, drawn on slices of copper as if he were working on the world’s largest available paper, though knowing well the secrets of telling his narrative with thirteen figures or more in a space that approximated or fell below the dimensions our printers were to abide by in this exhibition. “The Shell”*, a print I’ve returned to over and again with my students, begins as a simple cone shell against a white ground, and in succeeding states transforms itself into an ancient, elegant locomotive at rest in an abandoned, underground tunnel. Much of Rembrandt’s lesson lies in what we all know: a box seen as a box may appear as an object too small to step into; but that same box seen as an architectural structure can, through the power of visual organization, become a massive space with breathable air.

Rembrandt’s small prints (many 2” x 3”) were worked with the same openness and curiosity as his more rigorous images such as “Ecce Homo” and “The Three Crosses”. And yet the major large pieces are battlefields for ongoing change. The modifications are often vigorously dug directly on top of the narrative’s beginnings and are sometimes scraped away entirely, leaving only ghosts of first impressions. The miniatures, by contrast, seldom take a new route once begun. They are drawn with assurance, direct observation, and tenderness like swift studies in a master’s sketchbook. It is the incredible attention to touch, to sculpting as he draws through his ground, to the space dictated by the plate and to his alertness to his Dutch Mordant’s activity that encourages these small works to loom large. Nothing goes unattended. Nothing is cast off as the light in the tiny plate’s room beckons. It is something that is difficult to see unless you’ve observed the actual prints.

In the artist’s studio the miniature refreshes the monumental, and until quite recently it was utilized by almost everyone except the Abstract Expressionists (though DeKooning in the earliest years made small drawings, Kline returned to them in his middle years and Diebenkorn worked beautiful small representational drypoints and soft grounds). To illustrate his Pere Ubu series of miniature aquatint illustrations, Rouault charged his brushes with sugar lift ink and painted on copper. Goya, at age 79, on slivers of ivory that he covered with carbon, dropped a splash of water and searched for the nascent image, which he then developed as stunning monotype-like miniatures with little brushes. Durer, in his “Small Engraved Passion” cut with his burin what for me are his most moving engraved images. Rembrandt and Picasso (early on) used well-sharpened drypoint and etching tools. These tools and techniques were chosen in each artist’s studio to fit his own miniature staging areas, always as important to them as their major large work.

Exhibited in this show:

Sara Schleicher used tools that stumped me to complete her stunning series of umber monotypes which brought back childhood memories when I sat inside huge cocoons of fallen leaf piles in late October, lay back and looked through to the sky. But Schleicher adds another psychological element in the hidden growth with her hint of forewarning.

Harvey Breverman’s lively soft ground caricatures place us at talking distance to these famous men. In his tondo, in particular, we are very close to this head and remember where we sat in conversation. Breverman, as Rembrandt before him, knows touching distance, that is allowing his tool to believe it is actually on his figure.

Thom O’Connor’s lush, digital prints, probably the smallest images in the show, allow a long quiet stride through silver spaces between dark-figured trees, like walking through a perfectly balanced Morandi natura morte.

Jim Dormer in “Arezzo” moves with his burin through blinding Italian light invented by vibrations between the intersecting lines.

Sasja Lucas’ fresh, abstract monotypes set still life-like forms into landscape scale.

We walk on Mary Rose Griffin’s table between mixed media edibles defined subtly by drypoint. Her opened contours do not strangle the figures but build significant, substantial forms.

Thomas Seawell’s studio doors and Michael Arike’s handsome color etchings demonstrate strong beliefs in the miniature.

The size an artist assigns to each work determines the way we receive it. We hold the miniature to our faces or, if we can, place it in our lap. In a great print room with well-trained curatorial staff, the brilliant miniature possesses accessible open doors for one to enter privately. Our external environment should fall away so that we may read this image made, not with the whole body in motion, but rather with the tenacious pull of the fingers and wrist.

We thank Bev McLean for retaining the courage, enthusiasm and dedicated hours to have brought this exhibition to the Binghamton area year after year. She opened her home to these jurors and carefully unwrapped the prints and positioned them in alphabetical order by artist. It is not fashionable to sponsor a miniature print show; and the places that had become well known for theirs sadly, I believe, no longer participate. But some day they will again. Meanwhile, the belief in the miniature is kept alive in intimate, small circles.

Juror of selection and

awards